Economic Snapshot: A dramatic year for markets

2021/22 was another dramatic year for global financial markets. A combination of strong growth, abundant liquidity, supply chain blockages, and the Ukraine war triggered the biggest resurgence of inflation since the early 1980’s. Having been caught somewhat flat-footed by these developments, central banks started lifting interest rates in emphatic fashion to slow excess demand and stabilise inflation expectations.

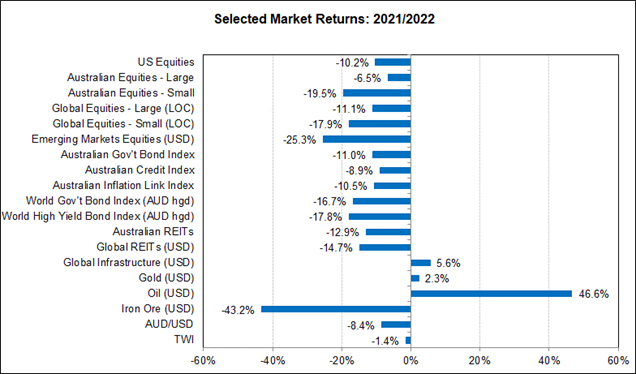

Both bond and equity markets, which had been trading on expensive valuations, were hit hard. Equities gave up all their gains since December 2020 and bonds posted some of their worst returns on record. Speculative instruments, including selected tech stocks and crypto currencies, fell very heavily.

While, geopolitical risks including any escalation of the Ukraine war which might directly involve a NATO country, as well as any move by China against Taiwan remain ever present. Were events, such as these, to escalate, it would be very bad for equities, but could see bonds rally on ‘safe-haven’ buying.

How 2022/23 turns out depends very much on how inflation evolves. The sooner inflation peaks and the faster it then falls, the sooner and faster higher interest rate expectations will decline. That would be good for bonds and equities. The opposite scenario of higher inflation for longer means interest rates would also be expected to be higher for longer, with greater risks of recession.

The initial impact to bonds and equities in that scenario would be negative, until the markets could see beyond any economic downturn where central banks may consider reduce interest rates again - this is some way off yet.

Chart 1: Higher inflation and interest rates caused losses across the board in 2021/22

Source: Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg 1 July 2022

Beginning of FY22

A year ago, we hoped that 2021/22 might be less eventful than 2020/21. Unfortunately, that did not turn out to be the case. Instead, markets have endured some of the most significant volatility in years. The key driver of this has been unbridled inflation and the flow-on implications that has for central bank monetary policy.

As the financial year started, economic growth around the world was running at a respectable pace and unemployment rates were still high enough to indicate there was some slack in labour markets. Inflation figures were starting to increase, but investors were not too worried. The inflation readings were not that high compared with recent years, and it was believed that growth would slow enough to alleviate any emerging inflationary pressures. This view was reinforced by concerns about possible lockdowns in response to new waves of COVID.

Monetary Policy: QE and Interest Rates

In this transitory environment, central banks around the world, including the Reserve Bank of Australia and the US Federal Reserve, began talking about “normalising” monetary policy. That is, the emergency settings of very low interest rates and Quantitative Easing (QE) programs that injected liquidity to sure-up confidence, would have to be unwound because they were no longer appropriate for economies that were recovering faster than expected.

A key aspect of returning to normal policy settings is getting cash rates back to neutral settings (somewhere between 2.5%-3.5%). That level is around where the economy can grow with stable inflation, and at the same time provide a positive cash rate and positive bond yields after adjusting for inflation. For example, through the worst of the COVID period, in the US the 10-year inflation-adjusted government bond was trading on a yield around -1%; not even in the GFC did these yields fall below zero.

At this stage, the central banks were separating the interest rate and QE decisions. They signalled that they intended to start removing QE first and then move on interest rates later. The RBA said it would not lift interest rates until inflation was sustainably back in the 2%-3% target band and that they did not expect that to be before 2024. The RBA believed higher inflation would require higher wages growth and that in turn meant running the economy fast enough to drive the unemployment rate below 4%.

Markets are always wary when central banks talk about tightening monetary policy. Higher cash rates and real yields are a threat to asset values, and in late 2021 bonds and equities were both expensive. Bond yields were very low and although equity price/ earnings (P/E) ratios had come off their post-COVID peaks, they were still very high by historic standards. Overall, bonds and equities, which are the mainstays of multi-asset portfolios around the world, were more vulnerable than usual.

The evolving data on inflation were mixed and central banks were still talking about inflation being a “transitory” problem. However, as 2021 closed it was becoming increasingly clear that the US labour market was so tight that meaningful wage inflation was occurring.

At the same time the price of oil was rising again, and markets expected to see oil prices around US$100/bl. When combined with ongoing supply chain problems, these factors led markets to the conclusion that US inflation was a bigger problem than previously thought and that, as a result, the Fed would have to raise interest rates faster and by more than previously expected.

Similarly, here in Australia the higher than excepted core CPI (inflation) result for the September quarter led to a sharp rise in interest rate expectations. The RBA held fast to its view of no rate increase before 2024, but the markets quickly lost faith in this.

Financial Markets

The developments outlined above, caused some volatility in financial markets in late 2021, but most assets still posted decent returns for the first half of the financial year. Developed equity markets rallied to new highs, but emerging equity markets fell under the weight of both regulatory reforms and harsher COVID lockdowns in China. Bond indices posted moderate losses as yields rose on expectations that central banks would have to tighten monetary policy sooner rather than later.

2022: Russian Invasion of Ukraine

Markets were increasingly nervous in the opening weeks of 2022, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February threw markets into disarray. Financial markets always dislike armed conflicts, but in this case the involvement of a global power of Russia’s stature elevated the risks significantly.

On top of this, the global supply of oil, wheat and other key commodities were disrupted, leading to sharp increases in their prices. For example, the oil price rapidly spiked to over US$120/bl and the price of wheat rose 60% in a matter of days.

Markets immediately saw the inflationary impact of this and revised up their expectations of inflation and interest rates. In coming months this was compounded by disappointing news on inflation in many countries, including Australia, the US, the UK and Europe.

Inflation

By this time, the whole inflation narrative had changed quickly and dramatically. It was no longer a question of normalising monetary policy but rather of the central banks being caught flat-footed and having to act much more aggressively to deal with what was rapidly becoming the worst inflation problem since the early 1980’s.

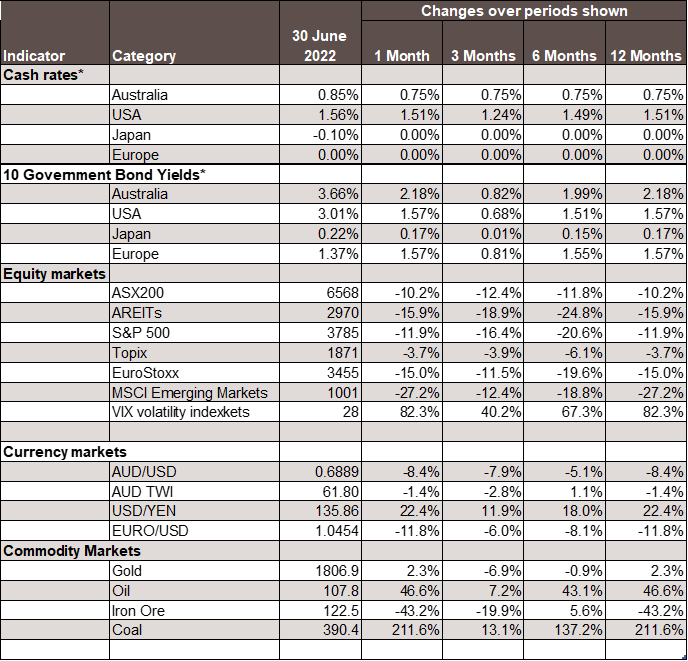

By mid-June, the markets were pricing mid-2023 cash rates of around 4% in the US and 4.5% in Australia. Cash rates like that would be well in excess of the neutral rate around 2.5% in both countries and would represent a significantly contractionary stance for monetary policy.

Cash Rates

A big risk in the current environment is that expectations of inflation get out of control and set off a wage-price spiral of the kind seen in the 1970’s and early 1980’s. Decisive moves by central banks are required to foster credibility and encourage the view that inflation will not persist.

In keeping with this the RBA raised the cash rate in May for the first time since November 2010, with a 0.25% move and followed this in June with a 0.5% move to bring the cash rate to 0.85%. The RBA also made it clear that more interest rate increases are on the way.

The US Federal Reserve lifted the cash rate three times between March and June, including a 0.5% move and one of 0.75%. Other central banks around the world, including Canada, the UK and Switzerland also started lifting their cash rates. Europe held off given the economic implications of the Ukraine war, but the ECB has been making plans to tighten monetary policy in 2022/23.

Cash rate increases of 0.5% - 0.75% in quick succession are serious moves designed to quickly unwind emergency monetary policy settings and to help anchor expectations of inflation. Markets were suddenly faced with a scenario combining negative growth shocks from the Ukraine war, China’s COVID lockdowns, and tighter global monetary policy.

Not surprisingly, the risk of recession became a major concern. Scope for central banks to come to the rescue with easy monetary policy, as they have so many times before, is off the table until the inflation problem has been fixed.

Financial Markets’ Response

This scenario of higher inflation, interest rates and bond yields, combined with weaker growth and possibly recession, is bad for markets, especially when those markets are trading at elevated valuations.

The last few months of 2021/22 saw equity and bond markets hit very hard. Bond markets posted losses of as much as 10% - 15% in the six months to June 2022. These are among the worst losses for bonds on record. Over the same period, equity markets fell far enough to wipe out all the gains made since the end of 2020.

The ASX 200 fared better than many offshore markets because of its exposure to commodities, the prices of which rose after the Russian invasion. US tech stocks fell sharply, as did speculative instruments like crypto currencies. By 30 June, Bitcoin had fallen 72% from its peak while some crypto-related businesses collapsed.

The price of gold spiked up to US$2,056/oz after the Russian invasion but has subsequently declined to around US$1,850/oz. The US$ rose in 2021/22 as markets expected the US Fed to be more aggressive with interest rates than other major countries. This helped push the A$/US$ down by 4% over the year to end at US$0.689.

Looking ahead: 2022/23

Gold

Among other assets, the price of gold looks expensive relative to real (bond) yields, and the A$/US$ looks cheap compared with current and expected interest rate differentials. In the coming year a lower gold price and a higher A$ may occur.

Geopolitical

Geopolitical risks will be important in 2022/23. It is hard to say how the Ukraine war will evolve, but if Russian aggression were to spill over into a wider theatre, almost inevitably involving NATO members, markets would take it very badly. Equities and non-US$ currencies would likely fall heavily.

China’s plans for Taiwan remain a perennial risk. Any moves by China on Taiwan would be very damaging to global equity markets. The A$ would likely fall sharply as well.

Inflation

Significant challenges will confront global markets in the coming year. The central issue is where inflation goes from here. The sooner inflation peaks and the faster it then falls, the sooner and faster interest rate expectations will decline. That in turn would mitigate fears about recession and a slump in corporate profits. Such a scenario would likely see both bond and equity markets rallying.

However, in the absence of recession risks we would not expect to see cash rates return to below neutral settings. That is, central banks would be able to complete the task of normalising monetary policy to neutral levels of cash rates which, while still low, will be higher than we have seen in recent years.

The opposite scenario of higher inflation for longer means monetary policy has more work to do beyond the normalisation task. Interest rates would be higher for longer, and above neutral which means the risks of recession escalate. The initial impact on bonds and equities would be negative until the markets could see beyond any economic downturn to central banks having scope to reduce interest rates back to neutral.

Where to from here?

Trying to pick the path of inflation from here is incredibly difficult. The dynamics of what drives inflation have changed significantly in the past year or so. On the one hand, futures markets are expecting commodity prices to decline further over the coming 12 months. That would ease pressure on headline inflation from food and energy prices, but underlying inflation is being driven more by labour market developments.

In the US, the Fed is trying to reduce the excess demand for labour, which is driving wage inflation, while here the RBA would like to keep the unemployment rate at or below 4% without sparking wage inflation above 3.5%.

Chart 3: Major Market Indicators – June 2022

*For cash rates and bonds, the changes are percentage differences; for the rest of the table percentage changes are used.

Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for the FMD Financial Economic Snapshot by Caravel Consulting Services Pty Ltd [AFSL 320842] and is intended to be a general overview of the subject matter. The document is not intended to be comprehensive and should not be relied upon as such. We have not taken into account the individual objectives or circumstances of any person. Legal, financial and other professional advice should be sought prior to applying the information contained in this document. Advice is required before any content can be applied at personal level. No responsibility is accepted by Caravel Consulting or its officers.

General advice disclaimer: This article has been prepared by FMD Financial and is intended to be a general overview of the subject matter. The information in this article is not intended to be comprehensive and should not be relied upon as such. In preparing this article we have not taken into account the individual objectives or circumstances of any person. Legal, financial and other professional advice should be sought prior to applying the information contained on this article to particular circumstances. FMD Financial, its officers and employees will not be liable for any loss or damage sustained by any person acting in reliance on the information contained on this article. FMD Group Pty Ltd ABN 99 103 115 591 trading as FMD Financial is a Corporate Authorised Representative of FMD Advisory Services Pty Ltd AFSL 232977. The FMD advisers are Authorised Representatives of FMD Advisory Services Pty Ltd AFSL 232977. Rev Invest Pty Ltd is a Corporate Authorised Representative of FMD Advisory Services Pty Ltd AFSL 232977.